Who wants to be King?

Why cities are desperate to host mega-events when it’s neither cheap nor easy.

Brisbane, where I live, was recently awarded the opportunity to host the 2032 Olympic Games. Successfully delivering a mega-event like this creates great excitement and anxiety for host cities and those who plan them. Marketing, money and ambition demand planning and spectacle at a grand scale.

Cities can only deliver successful mega-events and generate long-term benefits if wider forces align. Planning for a mega-event is rife with politics, community expectations and competition for resources. Despite their best intentions, cities may struggle to deliver if they are not given sufficient scope, resourcing, and political support.

Getting it right

Staging mega-events requires extra action across all the main areas of urban planning: infrastructure provision, transport, environment, housing, urban design, open space management and development control. The challenges of planning a mega-event across these domains are complex, time sensitive and additional to the core business of planning. Budgets are also supplementary and usually enormous.

Marketing, money and ambition demand planning and spectacle at a grand scale.

Maintaining good relations with communities is vital when planning for a mega-event. Planning for something like the Olympics can take 10 or more years, so planners need to build long-term rapport with local communities through stakeholder workshops and other participation media.

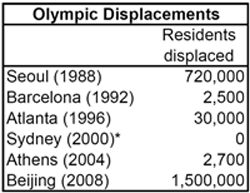

Of course, ignoring or trampling local communities sometimes happens too. Rio bulldozed favelas, while Beijing sought to displace hundreds of thousands and announced a ‘social cleansing’ operation aimed at beggars, prostitutes and hawkers.

The influence of politics is considerable in this space; sometimes communities can be engaged or alienated by political decisions taken without regard to proper planning. In such cases planners may struggle to rebuild community trust, or they may have to gently reduce community expectations if politicians have over-promised.

Best practice requires an overarching strategic plan that addresses the full breadth of priorities and requirements for hosting a mega event. It should detail how land will be found, how the infrastructure will be provided, transport connectivity, post-occupancy visions and budgeted implementation strategies. Individual precinct plans for new and existing venues and their surrounding areas can branch off from the main plan.

The most obvious and recognisable way for cities to leave a permanent mark on the urban landscape is with bespoke and visionary venues and precincts. Delivering new flagship venues is not only a design objective; it is immense value-laden effort for a single city to make a global statement. All host cities use this trick.

A particular hazard with this approach is event funding being cut during the development cycle. Shortfalls will often be met by siphoning from other municipal budgets. This poses serious challenges for the wider city, especially when mega-event plans were created based on higher budgets than those ultimately provided. It also risks a double negative return, where essential urban budgets are used to deliver venues and connected precincts of limited use to average citizens.

Winner and losers

The best mega-event venues and precincts – the ones that truly leave a legacy – combine high quality designs with adaptable functionality. Good urban planning, backed by strategic vision, is key to success. Planners must also ensure venues are accessible and have integrated visions of how they connect to surrounding areas, as well as legacy plans supporting their future use.

A strategic and visionary approach helps increase the potential for a city-wide uplift, including through urban regeneration projects. London leveraged the 2012 Olympic games for massive redevelopment of the post-industrial Lower Lea Valley. Barcelona delivered extensive inner-city brownfield redevelopment and other urban improvement projects. Remarkably, only 17% of expenditure for the 1992 Barcelona Games went towards sports, while 83% was allocated to urban improvement.

Planners in Sydney did an excellent job with the Sydney Olympic Park. An ambitious project, the stadium performed very well for the Olympics and has thrived since, hosting many high-profile sporting and cultural events every year. It is the centrepiece of a multi-use commercial and residential district. A simple legacy plan that did not try to change core use of the venue was a wise strategy. Sydney created 430ha of parkland, 40km of cycle paths and water recycling infrastructure.

Contrast Sydney with Beijing, where the famed ‘Bird’s Nest’ stadium wowed during the Games but failed to thrive afterwards. The plan to convert it to a shopping and entertainment complex never eventuated. The stadium is maintained at great cost but rarely used for anything. Worse again are examples of Olympic venues in Athens, which had no legacy plans at all, practically guaranteeing they would fall into ruin.

The pole-vault approach

Hosting a mega-event like the Olympics is a once-off opportunity to generate decades worth of urban uplift and marketing. Getting it right requires pace, commitment, stamina, vast amounts of money, and an absolute determination to deliver. Like a champion pole-vaulter, those cities that succeed make it look easy, while those who come up short have their failures displayed for all to see.

The cities that host mega-events are often remembered in the public mind long after the events themselves have been forgotten. That simple fact powers fierce global contests for hosting. The risk of failure might be significant but the potential for glory is still enough to keep many cities eager to give it a good go.