Urban planning has a long history of trying to master-plan ideal communities at various scales. Ranging from single districts to entire cities, masterplans tend to reflect the social, environmental and economic priorities of the time. Using them can bring order, coherence and certainty to urban development. Ignoring masterplanning can deliver buildings and spaces that do not perform as well as they should, lack coherence, and waste the potential of important sites.

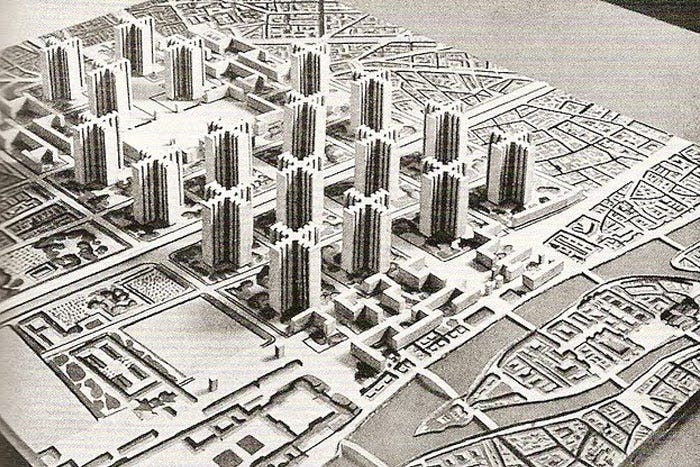

Planned communities based on the Garden City ideal from the early 20th century were proposed as a safe, healthy and prosperous alternative to the filth and squalor of industrialised cities. Masterplans based on Le Corbusier’s Radiant City vision were intended to create urban communities that mirror the precision and function of a machine.

Garden cities were rarely achieved at full scale. Of the living examples, Letchworth is probably best known at anything approximating a whole-of-city scale. Hampstead Heath is well known as a ‘garden suburb’ that incorporates some of Howard’s visions, most notably in terms of greenspace. The Radiant City became distorted into high rise social housing towers in many cities, many of which became isolated islands of privation, with few nearby services.

Urban planning priorities focused heavily on the suburbs after World War 2. This new focus was assisted greatly by the mass availability of cars. Suburbanisation quickly became the lifestyle of choice for most people. This is where contemporary masterplanned suburban communities come in. These are built at huge scale, transforming greenfield land into brand new suburbs over several years.

Masterplanned communities are based on integrated plans, designed to provide a range of social infrastructure as well as housing. Social infrastructure typically includes greenspaces, walking trails, bike paths, retail precincts, libraries, and childcare centres. Rather than just providing large clusters of housing with no supporting community infrastructure, master-planned communities can be thriving settlements offering many opportunities for positive social engagement.

Many planners see masterplanning as a beneficial and long-term approach to community building. Residents are often attracted by the immediate availability of services, and the knowledge that they are moving to an area with clear growth and development plans. It also helps if masterplans offer large volumes of housing across a variety of designs. This provides choice for a wide spectrum of buyers and allows residents to trade up or down within the area if they wish to.

While masterplanned suburban communities are often successful, many still have their shortcomings. A big one is a lack of local employment opportunities. Many rely on suburban service economies, an economic structure focused heavily on providing consumer services in the local area. The difficulty with suburban service economies is that they tend to offer lower-paid and often casual employment opportunities. They are also vulnerable to downturns when larger economic forces reduce people’s spending power.

A big problem with suburban service economies is they generally don’t offer lots of well-paid, steady, professional jobs – the kinds of employment people with mortgages often want. This means that despite some opportunities to work from home, many residents of master-planned suburban communities still regularly endure the regular commuter grind.

This dilemma also connects to a second shortcoming with many of these communities: a lack of public transport options, or under-use of the options provided. While some have nearby bus and train stations, accessing those stations is often only possible by driving. Providing parking for commuter traffic is an ongoing challenge. It’s easy to understand why residents might decide driving is a better option than jostling for parking at the train station before getting on a crowded commuter train. Not to mention that the cost of petrol may be comparable to a return bus or train fare.

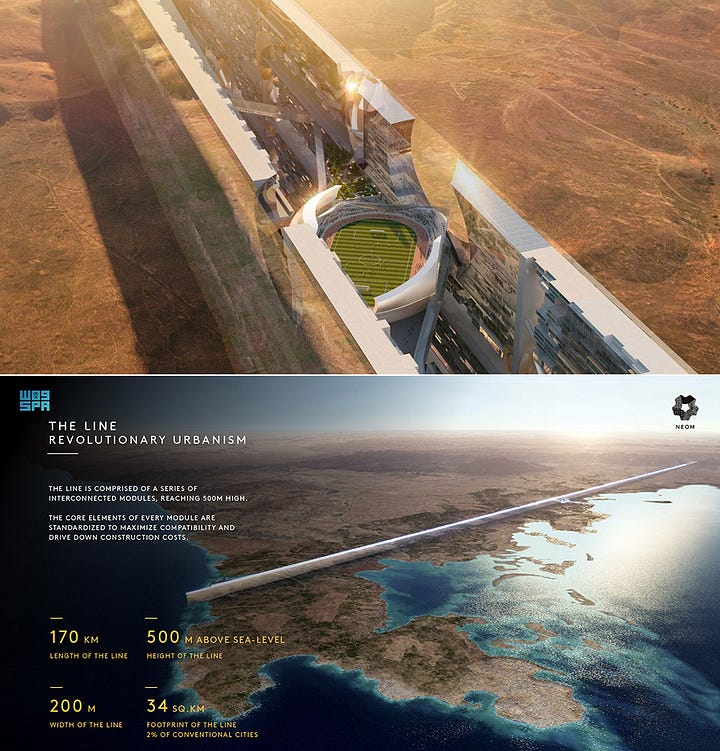

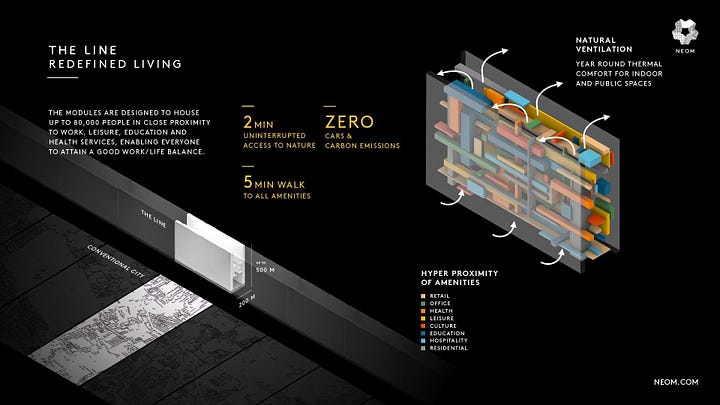

Masterplanned suburban communities will remain a planning priority into the future. When most residents want suburban living, planners will respond by trying to provide decent suburban options. Master-planning is a good way to mediate these aims. Master-planning full cities is also big business globally. Nusantara in Indonesia and The Line in Saudi Arabia are two very visionary and distinct projects underway currently. We will explore these examples more closely in a future article.

Whether it’s at the city scale, or the precinct scale, it is imperative to remember that a truly functional community should provide for the needs of its residents everyday – not just on the weekends when they’re off work.

Super post. I’m really looking forward to the follow up pieces. Great that you’ve touched on the historical antecedents of modern master planned communities in British garden suburbs and new towns. This was explicit in the case of Canberra’s new towns but I think is also obvious with contemporary new communities like Forest Lake, North Lakes, Springfield and Yarrabilba. Also fair to point out that establishing significant centres of tertiary service employment in MPCs remains a challenge.. Varsity Lakes has a high proportion of home based employment of this type as well as a mixed use business park that accommodates jobs that have moved from Southport and Bundall. That could be a model for future MPCs. As populations have suburbanised, so has industry, so many resident workers find jobs in eg transport and logistics in outer suburban industrial areas. Most outer suburban communities have relatively higher proportions of technical trade skill employment (‘tradies’) whose work location varies widely, so a smaller proportion of workers are involved in a CBD bound commute than many imagine.

As I’ve suggested previously, please keep up the good work!